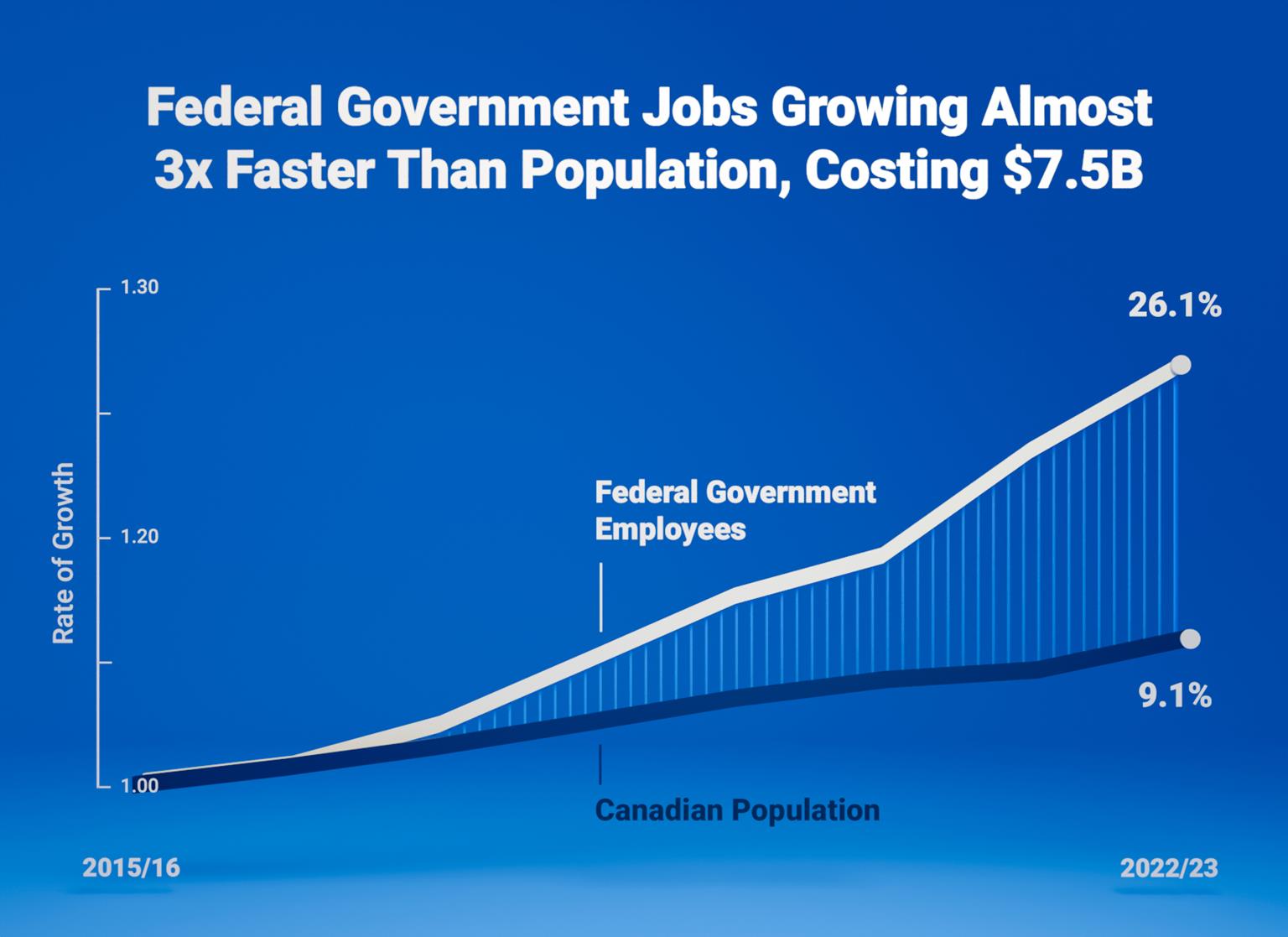

Hiring by the federal government in excess of population growth cost taxpayers $7.5 billion in 2022/23

By: Ben Eisen and Milagros Palacios

In recent years, Canada’s federal government has substantially increased spending. In its 2024 budget, the government estimated program spending (all expenditures aside from debt service) will be $483.6 billion in 2024/25 (Canada, DOF, 2024). On an inflation-adjusted per-capita basis, this represents a 28.0 percent increase from 2014/15. This spending growth has contributed to persistent federal deficits (Fuss and Ryan, 2022). Personnel spending represents approximately 49 percent of the federal government’s ongoing operating costs (PBO, 2024).1 As such, the evolution of the size and cost of government employment is an important dimension of Canadian public finance. This essay examines the role of expanding federal government employment as a contributing factor to spending growth and budget deficits since 2014/15.

Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) provides regular updates on the size and compensation costs of the federal public service. This essay uses PBO data and population data from Statistics Canada to examine changes in the size of the public service and the growth of public sector compensation costs. The most useful single measure of the size of the federal public service is Full-Time Equivalents (FTE). This measure captures the workload of a full-time employee. It allows the data to adjust for changes in the composition of the workforce with respect to the shares of full- and part-time employees. We use fiscal year 2014/15 as the baseline for our analysis because this was the final year of a reduction in the size of the federal workforce that had been occurring since 2010. In 2015, there was a directional shift, and the federal workforce began to grow. The size of the federal workforce has increased every year since then until the final year of available data which is FY 2022 (PBO, 2024). Over the course of this period, federal employment increased by 26.7 percent.

This growth in the size of the federal government workforce has occurred during a time of significant population growth. To account for this source of potential upward pressure, we have calculated the number of FTEs employed by the federal government per 1,000 Canadians each year. It shows that in 2014/15, there were 9.6 federal FTEs for every 1,000 Canadians. In 2022/23, that number had increased to 11.1. This means that relative to the size of the population, the federal workforce has increased by 15.7 percent.

The discussion in the previous section demonstrated that government employment has increased considerably faster than the Canadian population over the past decade. This section seeks to provide insight on the impact of this employment surge on overall federal spending and therefore on the size of the budget deficit. We conduct this analysis through a thought experiment, considering an alternative scenario in which the growth in government employment since 2014/15 had been held to the rate of population growth. We then multiply the difference in FTEs by the average cost of each federal employee to obtain an estimate of the savings in the final year of analysis. I GROWING GOVERNMENT WORKFORCE PUTS PRESSURE ON FEDERAL FINANCES BY BEN EISEN AND MILAGROS PALACIOS Figure 1: FTE Personnel per 1,000 Canadians from 2014/15 to 2022/23 9.6 9.6 9.6 9.7 9.9 10.2 10.3 10.8 11.1 8.5 9.0 9.5 10.0 10.5 11.0 11.5 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2021/22 2022/23 Number of FTE per 1,000 © 2024 Fraser Institute fraserinstitute.org

It shows that total federal employment has increased from 340,669 FTEs in 2014/15 to 431,537 FTEs in 2022/23. In the alternative scenario, shown by the red perforated line, federal employment would have increased far less. In this scenario, federal employment would have risen to 374,367 in 2022/23. This means that there were 57,170 more federal employees in 2022/23 than there would have been in the alternative scenario. Using PBO data on the per-FTE cost of public employment, we can produce an estimate of the savings that would have been achieved by holding the rate of growth in the federal government’s employment to the rate of population growth across Canada. The PBO reports that the per-FTE cost of federal employment in 2022/23 was $130,853. (This figure includes wages/salaries plus the cost of employer provided benefits.)

If we multiply this figure by the gap in the number of FTEs shown in the previous section, we can see the savings that would have been achieved in the final year of this analysis. The result of this calculation shows that if federal employment had been held to the rate of population growth since 2014/15, spending on the government’s wage bill would have been $7.5 billion less than it actually was in 2022/23. There would have, of course, also been savings in prior years. This represents a substantial potential source of savings. The federal deficit in 2022/23 was $35.3 billion. The analysis here suggests that holding federal employment to the rate of growth since 2014/15 would have shrunk the deficit by $7.5 billion. This would have represented a 21.2 percent decrease in federal deficit for that year.

This essay shows that one contributing factor to the federal spending growth and persistent deficits of recent years has been a rising compensation bill for employees. The number of FTEs per 1,000 Canadians has increased by 15.7 percent federal since 2014/15. If the government seeks to reduce the deficit by reducing its compensation bill, returning to pre-pandemic staffing levels or working to move closer to staffing levels from the baseline year of this analysis could achieve substantial savings. Government spending on information technology has also increased significantly in recent years, largely for consultants. One measure of the value of these expenditures could be the extent to which they enhance the productivity of the government workforce and help slow the growth of government employment. The federal government has announced a plan to reduce the federal workforce by 5,000 positions through attrition over five years. This would be a directional change, but it would be insufficient to reverse the growth in the federal service that has occurred since 2014/15. In addition to reducing the number of government employees, the government should also consider a careful review of compensation policies to assess whether the per-employee cost can be reduced. A 2021 analysis showed that government sector employees in Canada (at all levels) enjoy a wage premium of 8.5 percent compared to comparable workers in the private sector (Palacios et al., 2023). A review of compensation levels for federal employees would be useful to determine whether federal workers enjoy a pay premium over similarly qualified private sector employees.

This essay has documented that in recent years the ratio of federal government workers to the population has grown significantly. Further, it has shown that this growth in the size of the public sector workforce has contributed to a significant increase in compensation costs for the federal government and therefore to the budget deficit. Specifically, it demonstrates that if the federal workforce in 2022/23 had been the same size (relative to population) as in 2014/15, the 2022/23 deficit would have been $7.5 billion lower, a decrease of 21.2 percent.

https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/growing-government-workforce-puts-pressure-federal-finances

The result of the work of these bureaucrats will be for another essay. But the damage we can see everywhere around us.

DB