An Analysis of Agenda 2030

People are talking increasingly about Agenda 2030, but what exactly is it? Basically it is a 35-page document produced by the United Nations entitled Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which sets out seventeen goals to be achieved by 2030. Above the goals hover overarching aims, which are not only frighteningly utopian but read as though formulated by an ill-educated child.

According to the document’s first paragraph, the Agenda seeks to “strengthen universal peace in larger freedom”.[1] What is larger freedom, how can you strengthen universal peace in it and how are you going to get universal peace to start with? The paragraph then says that “eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is … an indispensable requirement for sustainable development”. Why mention extreme poverty if you’re going to eradicate poverty itself, how are you going to eradicate it, and what does this have to do with sustainable development, whatever that is? A few paragraphs later, the Agenda envisages “a world free of … disease and want”.[2] Think of that! No more disease! No more unmet desires! This is frightening because although such aims will never be achieved there is no telling what horrors might be created in the attempt, and the attempt is being made. It has been going on since 1st January 2016, when the Agenda came into effect having been adopted a few weeks earlier by 193 countries at the UN General Assembly.

Structurally the Agenda is something of a dog’s breakfast. In a section entitled “Declaration”, heads of state resolve to “end poverty and hunger everywhere”, but this is not one of the goals. They come later, the first being to end poverty in all its forms everywhere, the second being to end hunger. The Declaration contains 53 numbered paragraphs and is followed by a section running from Paragraph 54 to Paragraph 17.19. The third section starts at Paragraph 60. Such is the competence of the body to which the world’s governments have surrendered their autonomy.

A begging operation

In keeping with the world-wide fashion, Agenda 2030 is preoccupied with race and sex. To start with race, it distinguishes “developed” countries from “developing” and “least developed” ones, where by “developed countries” it means the countries of the West, inhabited by white people, plus Japan. By “least developed countries” it means mainly those in sub-Saharan Africa, which is where 35 of the 48 countries identified as least developed are located.[3]

It is in effect addressed to the developed countries, being largely a list of things they will do for the others. Thus when it says that its goals “involve the entire world, developed and developing countries alike”, it does not see the goals as involving the two sides in quite the same way.[4] It is for developed countries to achieve the goals and for developing countries to enjoy the achievement.

According to the Agenda, the goals resulted from a lengthy and intensive consultation which “paid particular attention to the voices of the poorest and most vulnerable”.[5] The West has therefore acquired goals set for it largely by sub-Saharan Africa. The Agenda emphasises the “special challenges facing the most vulnerable countries and, in particular, African countries”.[6] It does not appear to see it as the task of Africans to address these challenges. That is a job for the West.

Its provisions for economic growth were drawn up taking into account “different levels of national development and capacities”.[7] This appears to assume that black people lack the capacity to create economic growth, which must be brought to them by white people. Similarly, it is presumably for the West to make sure that “no one will be left behind”,[8] which it must presumably do either by speeding other countries up or slowing itself down. Similarly again, the statement that countries will “endeavour to reach the furthest behind first” is clearly aimed at white countries since it would make little sense to expect a country lagging far behind to do much for one lagging even further behind.

Unsurprisingly in view of its Marxist character, the Agenda is preoccupied with equality, as in Goal 10, which is to “reduce inequality within and among countries”.[9] This is to be done by “sharing” wealth, meaning transferring it from rich to poor.[10] It therefore gives “developing” and “least developed” countries an incentive to be as poor as possible, thereby maximising their entitlement to the wealth of others.

And so the Agenda resembles a contract drawn up by a broker to be signed by the benefactors of a beggar. Noticing how the sight of the beggar fills his benefactors with guilt and pity, the broker exploits these emotions in the contract, which sets the terms on which the wealth of the one will be transferred to the other. He has inserted a clause stating that the benefactors must keep on giving until the beggar has as much as they do, which will never happen by the beggar becoming rich, for all that he is given soon disappears. It will only happen by the benefactors becoming as poor as the beggar, an outcome to which the broker eagerly looks forward, for he hates the benefactors for their success. He gets them together to sign the contract, which they duly do. The “equality” clause doesn’t bother them. They like the idea of equality.

African children begging

The begging operation implied by Agenda 2030 reflects the natures of the participants. White people have shown themselves to be a soft touch, and sub-Saharan Africans are well versed in begging. According to one 19th-century explorer, Africans of all classes were most pertinacious beggars.[11] Another reported that they would ask for something claiming it was for a sick wife or daughter and if given it would ask for more: one’s hat, one’s neckcloth and then one’s coat.[12] It was not beneath an African king to beg, wrote a third in 1870, who related how one such person had demanded his highland costume, then his watch, his compass and his rifle.[13] A fourth stated that an African’s first question on meeting a white man was “What will you give me?”[14] Africans wanted everything for nothing, wrote a fifth, who was approached by fifteen or twenty Africans every day, “all begging, and often after a very cunning fashion”.[15],[16]

Black people still beg compulsively. In majority-white countries we see it in their demands for special treatment. They are black, therefore they should be given a promotion or a place at Oxford University, nor should they be stopped and searched by the police. They expect the benefits of affirmative action, diversity quotas and the like. Nor is it unknown for African leaders to comment on the begging of their co-racials. In December 2022 the president of Ghana urged other African leaders to stop begging from the West.[17] In April 2023 the Rwandan president asked an audience of Rwandans: “Can somebody tell me why we have become beggars?”[18]

The Black Lives Matter disturbances of 2020 were a begging operation, aimed at filling white people with such guilt and pity that they would give money to the organisation and grant black people even more special treatment than they were already receiving. The reparations-for-slavery movement is another begging operation, again intended to arouse such guilt and pity in whites as to make them give blacks large amounts of money. The UN is playing the same game.

As time goes on, it will increase the pressure. Indeed, it started doing so less than four years after the Agenda came into effect. In the foreword to a progress report published in 2019, the UN Secretary-General wrote that although favourable trends were evident in some areas, in others “urgent collective attention” was needed. A “much deeper, faster and more ambitious response” was required.[19] “Give more! Give faster!” was his message to the West. Also digging his spurs into the sides of whites, Liu Zhenmin, a senior UN official, wrote that some areas required “urgent attention and more rapid progress”.[20] He too felt that whites were not stepping up to the mark briskly enough.

A defining issue of our time, Liu Zhenmin went on, was increasing inequality. Poverty, hunger and disease continued to be concentrated in the world’s poorest countries. This raises the question of why these countries are still poor when the West has given them hundreds of billions of dollars in the recent past. Shouldn’t this have led to some development? If the aid was ineffectual, why should more be given? But Liu Zhenmin seemed to think that problems persisted because the West’s donations were insufficient. He wrote in slogans: these were global problems that required global solutions, meaning that they were problems in one part of the world that must be solved by people in another, who were not doing enough about them.

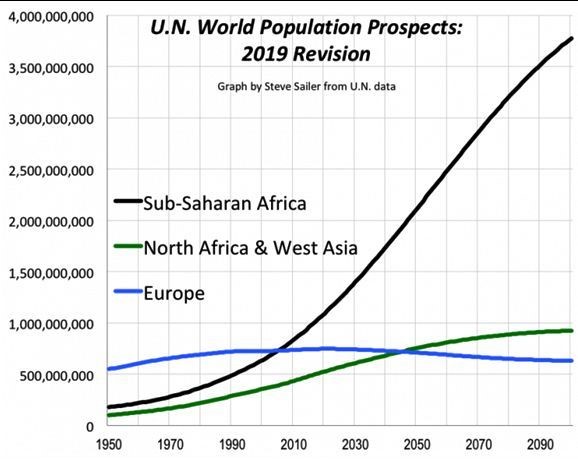

But the West’s charity has had one effect: Africa’s population explosion. Whereas in 1950 there were 200 million Africans, today, thanks largely to food and medicine from the West, there are 1.4 billion. According to UN projections, by 2040 there will be two billion, and by the end of the century four billion, twenty times as many as in 1950.

Most new Africans will want to come to Europe, where they will expect free housing, free medical treatment and a certain amount of spending money. Those who reach Europe will be accepted, doubling its population and bankrupting it by the cost of looking after them. It will end the century as poor as Africa, which it will also resemble in being ridden by crime, dereliction and disease. This will be a triumph for the UN, for international inequality will have been reduced.

Graph by Steve Sailer showing past and projected populations using UN figures[21]

Feminism

Coming to the theme of sex, men and boys have much to fear from Agenda 2030. One of its goals is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”;[22] another is to “Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life”.[23] Under a food-related goal, by 2030 “the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women”, will be doubled.[24]

It goes on. Resources will be devoted to “supporting smallholder farmers, especially women”. The Agenda will ensure “that women have a role in peacebuilding and State-building”,[25] that women and girls enjoy equal access to economic resources and political participation,[26] and that safe and secure working environments are provided for all, “including migrant workers, in particular women”.[27] Not only will open defecation be ended, “paying special attention to the needs of women and girls”,[28] but the nations of the world will promote “shared responsibility within the household and the family” — except, that is, for nations where traditional family structures must be respected, or as the Agenda puts it, where abolishing them would not be “nationally appropriate”.[29] Says the Agenda: “All forms of discrimination and violence against women and girls will be eliminated”.

The Agenda expresses no disapproval of discrimination against men and boys. Indeed it implicitly demands it in calling, as repeatedly in the quotes above, for discrimination in favour of women and girls. Moreover, how will women’s full participation in leadership be achieved if the sexes are treated equally? The participation will have to be engineered by sex discrimination. And given that by “gender equality” is meant equality of circumstance, how can this be created without more sex discrimination?

Expanding on the concept of shared household and family responsibilities, Liu Zhenmin states that women and girls “perform a disproportionate share of unpaid domestic work”.[30] For shame! Women looking after children or elderly members of the family, helped by their daughters? Women and girls taking care of the home and not being paid for it? Thank the Lord for Agenda 2030, which will put an end to such abominations, at least where nationally appropriate!

The Agenda in effect

Feminism

The effects of Agenda 2030 are all around us. Discrimination in favour of women was of course routine in the West long before Agenda 2030 came along, but it was rarely exhibited as openly as by Donald Trump when he promised to nominate a woman for the next available place on the Supreme Court or by Joe Biden when he vowed to choose a female running-mate, both in 2020. In the same year Boris Johnson indicated that the Conservatives would seek to make half their MPs women, an objective later confirmed by the party’s chairman, which will clearly require sex discrimination.[31] Thus our leaders are “empowering” women and giving them “equal access to political participation”.

In March 2023, Britain’s International Development Minister explained how the UK had used its £11 billion foreign-aid budget, boasting that it was a “leading global player” in “development”.[32] His department had announced an International Women and Girls Strategy, “which put gender equality at the forefront of UK foreign policy”. At least eighty per cent of Britain’s bilateral aid would go on such matters as gender equality by 2030. More immediately, Britain would spend £200 million on a women’s project in sub-Saharan Africa and give £38 million to “women’s rights organisations around the world to advance gender equality”.

Education

The politicisation and general decline of Britain’s education system has much to do with Agenda 2030. What Goal 4 — “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education”[33] — means in practice, wrote Freya Laidlow-Petersen, a recent school leaver, is a “push to standardise children with the same worldview and the same limited knowledge and capacity for independent thought”.[34] Already before Agenda 2030 the UN was advocating a global programme aiming to “restructure education and society” around the world, which proposed concepts such as “global citizenship”, “social justice” and “diversity” as providing a “framework” for all subjects taught in schools. Freya Laidlow-Petersen mentioned a leading exponent of “development education” in Britain who sees politicisation as a proper aim of schooling,[35] and reported that since 2013 Britain’s ministers of education have increasingly added the “global dimension” to the national curriculum, something that will only have been stepped up under Agenda 2030.

She stated that on her A-level English Literature course, students were not required to read the books; it was enough for them to memorise the plot summaries and quotations given them on handouts and to employ the terminology of post-colonialism, postmodernism, feminism and Marxism in essays about such questions as whether Shakespeare was a misogynist. Literary appreciation, let alone critical thinking, did not come into it. Under the influence of Agenda 2030, schools did not educate children so much as “stunt them in their cognitive ability”.

Locally

Agenda 2030 applies not just at the national, supra-national and global levels but also locally. Governments “will work with local authorities and communities to renew and plan our cities”.[36] This is a reference to the “fifteen-minute cities” being piloted in such places as Oxford and Canterbury, where residents are discouraged from using their cars by electronically operated barriers that require a permit to get through, by fines levied on drivers who make previously innocent journeys, and by massive plant pots placed in the middle of the road.

Unknown city, England

The marketing of such measures is not compelling. We will not feel confined in our fifteen-minute cities, we are assured, because everything we could want will be within a fifteen-minute walk. Yet nothing is being done to make this a reality. The hundreds of hospitals that would need to be built to place one within a fifteen-minute walk of every city dweller’s house are not being planned, nor has it been explained how shops catering for the needs of specialists such as embroidery enthusiasts, woodworkers or keepers of decorative fish will appear within a fifteen-minute walk of wherever they might live. Nor has it been explained by what magic the venue of every choir, chess club or the like will bring itself within this distance of every member’s house.

Another reason given for welcoming “fifteen-minute cities” is that they will reduce commuting times, the idea appearing to be that those who must drive to work because it is too far to walk will find the roads comparatively deserted.[37] How this will happen when the other drivers who used to be on the roads will still be there because they too must drive to work remains a mystery.

But the Agenda-2030-minded people behind such initiatives can think of no better ways of selling them, nor does any cost to citizens seem to them too great as long as they can persuade themselves that any resulting reductions in carbon emissions will serve a higher goal.

Other effects

Such effects of Agenda 2030 point to its other side, where it is less concerned with developing the Third World than with crippling the First. Further effects of this kind, to draw on an article by the policy analyst Tom DeWeese, include the following.[38]

Our diet is being increasingly controlled, with meat to be replaced by plant- or insect-based alternatives. See Goal 3: “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being”. Our industries continue to be shut down and moved abroad. See Goal 9: “Promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization”. There appears to be a plan to move us all into rented city apartments. See Goal 11: “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”.

According to DeWeese, California’s pastures are reverting to deserts thanks to Goal 6: “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation”, which has entailed taking down water systems and dams to “free the rivers”. California has seen forest fires like never before thanks to Goal 15, which requires the “sustainable” management of forests. This has meant prohibiting the removal of dead trees from the forest floor, making it a tinder-box. Why is the use of oil being phased out in favour of less reliable and more expensive wind and solar power? Goal 7: “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy”.

More generally, plans are afoot to scrap everything a civilisation depends on in the name of changing the behaviour of the very heavens, as in Goal 13: “Take urgent action to combat climate change”. On this subject DeWeese quotes Timothy Wirth saying as president of the UN Foundation: “We’ve got to ride this global warming issue. Even if the theory of global warming is wrong, we will be doing the right thing in terms of economic and environmental policy”.[39] As long ago as 1992, Maurice Strong as chairman of the UN’s Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro asked: “Isn’t the only hope for the planet that the industrialised nations collapse? Isn’t it our responsibility to bring that about?”[40], [41]

It is hard to believe that the authors of Agenda 2030 or their followers are merely misguided. Their words and deeds tell us that, like the imaginary broker, they are motivated by a burning hatred of the West and an implacable urge to destroy it. This is the “transformation” they intend to visit upon the world.

The term “sustainable development”

It is through sustainable development that they propose to bring about this transformation, as made clear by the full title of Agenda 2030. Yet when reading the document it can be hard to see what its contents have to do with sustainable development if by this is meant development that can be sustained. How does industry become sustainable by being moved from West to East? In what way can a fifteen-minute city be sustained any better than a normal one? How is a water-management system made sustainable by being dismantled? And how are wind and solar power any more sustainable than power from fossil fuels, of which reserves at present rates of consumption would last us 3,000 years and which grow all the time as more are found and improving technology enables more to be exploited?[42]

We might therefore ask what is really meant by “sustainable development”. In the Third-World context, the word “development” does not refer to a process through which a “developing” or “least developed” country might go naturally, getting as far as its talents and efforts allow, which is how the West developed. Rather, it refers to something done to it by the West, which principally distributes money, food and medical supplies.[43] As for “sustainable” in this context, perhaps the UN should have said “sustained”. What “sustainable development” in the Third World means is that the West must sustain its development efforts and not slack.

When it comes to the First World, the UN has a difficulty in promoting sustainable development since the West’s development is clearly sustainable already, having been sustained for thousands of years. But for the UN, the sustainability of the West’s development is precisely the problem. What the UN wishes to see is the termination of this development or preferably its reversal, which might enable other countries to catch up, hastening the advent of international equality. But how can the West be persuaded to terminate or reverse its development in the name of sustainable development? The UN’s answer is to change the subject at this point from sustaining one’s development to sustaining something else, namely the very planet. For the West, “sustainable development” means hobbling itself in the name of combating the invisible catastrophe of climate change, for which it is allegedly responsible.

But one can only go so far in trying to penetrate the meaning of the term “sustainable development”, which the UN’s document must try to obscure. Why else, although it uses the term more than a hundred times, does it not define it? It must keep the meaning unidentifiable lest the document’s contents be appraisable in the light of a stated purpose. If we knew what “sustainable development” meant, we could ask how this or that goal will contribute to it.

And so the UN chooses a term that sounds good. It sounds good to say, as the document does in the preamble, that sustainable development cannot exist without peace any more than peace can exist without sustainable development, although this is meaningless.[44] It sounds good, albeit ungrammatical, to say that enabling environment at the national and international levels is essential for sustainable development.[45] To say that the interlinked and integrated Sustainable Development Goals will profoundly improve the lives of all is a good-enough sounding statement to fool some people.[46]

Conclusion

The UN’s Agenda 2030 is a purpose-built weapon aimed at the West and especially its men, seeking in the first place to exploit the fact that white people’s compassion now exceeds their common sense — as it did not do 150 years ago, when they could see begging for what it was — so as to fleece them. Secondly it attempts to arrest or reverse the West’s development, apparently with the aim of bringing its civilisation to an end. Compatible with both aims are those of every other globalist organisation from the World Economic Forum to the World Bank and the World Health Organisation. Our formidable task is to resist all these parties, as well as our complicit governments,[47] if we are not to descend into the envisaged utopia.

[1] For Agenda 2030 see (1) https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda or (2) https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/pdf/N1529189.pdf.

[2] Agenda 2030, Paragraph 7.

[3] United Nations, 2014, “Country classification”, https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_current/2014wesp_country_classification.pdf.

[4] Agenda 2030, Paragraph 5.

[5] Agenda 2030, Paragraph 6.

[6] Agenda 2030, Paragraph 56.

[7] Conditions will be created “for sustainable, inclusive and sustained economic growth … taking into account different levels of national development and capacities” (Paragraph 3). The Agenda will be implemented “taking into account different national realities, capacities and levels of development” (Paragraph 21). “The Sustainable Development Goals … [take] into account different national realities, capacities and levels of development” (Paragraph 55).

[8] Agenda 2030, Paragraph 4.

[9] See also Agenda 2030, Paragraph 13.

[10] Agenda 2030, Paragraph 27.

[11] On p. 84 HH quotes Sir William Harris, 1843, Major Harris’s Sports and Adventures in Africa, p. 299. In this note and those directly below, “HH” refers to Hinton Rowan Helper, 1868, The Negroes in Negroland, New York: G W Carleton, available at https://ia902606.us.archive.org/6/items/negroesinnegrola00helpiala/negroesinnegrola00helpiala_bw.pdf.

[12] On p. 84 HH quotes Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming, 1850, Five Years of a Hunter’s Life in the Far Interior of South Africa, Vol. I, p. 128.

[13] On p. 34 HH quotes Samuel Baker, 1870, The Great Basin of the Nile, p. 313 and 386.

[14] On pp. 82-83 HH quotes “Burton’s Africa”, p. 493, which could be any of Burton’s books about Africa, most of which were first published in the 1860s.

[15] On p. 87 HH quotes “Krapf’s Africa”, p. 175, which is presumably a book by John Ludwig Krapf (1810-1881).

[16] These writers were referring to Bantus, and not all black people are like Bantus. Christopher Columbus described the Arawaks of the West Indies as noble and kind, which he would not have done had he found them to be pertinacious beggars. See B:M2022, Feb. 12th 2021, “Taíno: Indigenous Caribbeans”, https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/pre-colonial-history/taino-indigenous-caribbeans/.

[17] africanews, Dec. 14th 2022, “Ghana’s president Akufo Addo urges Africa to stop ‘begging’”, https://www.africanews.com/2022/12/14/ghanas-president-akufo-addo-urges-africa-to-stop-begging/. See also GhanaWeb, Dec. 15th 2022, “Stop being beggars — Ghana president to African leaders”, https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/africa/Stop-being-beggars-Ghana-president-to-African-leaders-1680637.

[18] Africa Web TV, April 3rd 2023, “Can We As Africans Stop Preparing Ourselves To Becoming Someone’s Breakfast? | President Paul Kagame”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bRy69WPRJ-A.

[19] United Nations, 2019, António Guterres’s Foreword to “The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019”, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/#sdg-goals.

[20] United Nations, 2019, Liu Zhenmin’s Introduction to “The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019”, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/#sdg-goals.

[21] V Dare, July 17th 2019, “Sailer In TakiMag: 2019 Most Important Graph in the World”, https://vdare.com/posts/sailer-in-takimag-2019-most-important-graph-in-the-world.

[22] Agenda 2030, following Paragraph 59.

[23] Agenda 2030, Goal 5, Paragraph 5.5.

[24] Agenda 2030, Goal 2, Paragraph 2.4.

[25] Agenda 2030, Goal 2, Paragraph 2.3.

[26] Agenda 2030, Goal 5, Paragraph 5.6 (a).

[27] Agenda 2030, Goal 8, Paragraph 8.8.

[28] Agenda 2030, Goal 6, Paragraph 6.2.

[29] Agenda 2030, Goal 5, Paragraph 5.4.

[30] United Nations 2019, op. cit., Liu Zhenmin’s Introduction.

[31] Telegraph, April 30th 2022, “Half our MPs will be women, pledge Tories after Neil Parish porn scandal”, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2022/04/30/half-mps-will-women-pledge-tories-neil-parish-porn-scandal/. The Labour party adopted all-women shortlists in 1997.

[32] GOV.UK, March 16th 2023, “Andrew Mitchell reaffirms the UK’s commitment to helping the world’s poorest”, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/andrew-mitchell-reaffirms-the-uks-commitment-to-helping-the-worlds-poorest.

[33] See also Agenda 2030, Paragraph 25.

[34] Freya Laidlow-Petersen, no date (accessed Dec. 2022), “The Politicising and Degeneration of our Education System”, https://www.newcultureforum.org.uk/freya.

[35] This was Douglas Bourn, Director of University College London’s Development Education Research Centre.

[36] Agenda 2030, Paragraph 34. See also Paragraphs 45 and 52.

[37] Oxfordshire Guardian, Jan. 26th 2023, “Oxford: The 15-Minute City Low Traffic Neighbourhood (LTN)”, https://oxfordshireguardian.co.uk/oxford-15-minute-city-low-traffic-neighbourhood-ltn/.

[38] Redoubt News, Oct. 20th 2017, “AGENDA 21/AGENDA 2030 THERE IS NO DIFFERENCE” (which contains a reissue of Tom DeWeese’s 2015 article “It’s 1992 All Over Again. A New Agenda 21 Threatens Our Way of Life”), https://redoubtnews.com/2017/10/agenda-21-2030/. DeWeese based his appraisal of Agenda 2030 on the effects of the UN’s Agenda 21, which came out in 1992.

[39] According to Watts Up With That?, June 25th 2011, “Bring it, Mr. Wirth — a challenge”, https://wattsupwiththat.com/2011/06/25/bring-it-mr-wirth-a-challenge/, the quotation is taken from Michael Fumento, 1996, Science Under Siege, p. 362.

[40] This quotation is also given by Geller Report, May 17th 2021, “World Economic Forum Chairman: “Isn’t The Only Hope … That the Industrialized Civilizations Collapse?”, https://gellerreport.com/2021/05/world-economic-forum-chairman-isnt-the-only-hope-that-the-industrialized-civilizations-collapse.html/.

[41] Similar quotations, again predating Agenda 2030, include: (1) “No matter if the science of global warming is all phoney … climate change provides the greatest opportunity to bring about justice and equality in the world” (Christine Stewart, former Canadian Minister of the Environment); (2) “In searching for a new enemy to unite us, we came up with the idea that pollution, the threat of global warming, water shortages, famine and the like would fit the bill. All these dangers are caused by human intervention … The real enemy then, is humanity itself” (Club of Rome); (3) “[W]e have to offer up scary scenarios, make simplified, dramatic statements and make little mention of any doubts … Each of us has to decide what the right balance is between being effective and being honest” (Prof. Stephen Schneider, lead author of many IPCC reports); (4) “The data doesn’t matter. We’re not basing our recommendations on the data” (Prof. Chris Folland, Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research); and (5) “It doesn’t matter what is true, it only matters what people believe is true” (Paul Watson, co-founder of Greenpeace). Source: Standard-Examiner, Dec. 1st 2014, “Climate change quotes not often heard in media”, https://www.standard.net/opinion/letters/2014/dec/01/climate-change-quotes-not-often-heard-in-media/.

[42] Alex Epstein, 2014, The Moral Case For Fossil Fuels, New York: Portfolio / Penguin.

[43] The other main business of the development industry is trying to make non-white countries more white-like. They must stop offending white people, who don’t like to see people of other races being poor and unproductive. Infrastructure must be installed that white people would want, whether or not it will be used, such as sanitation systems in African villages that have not asked for them. Efficiency must be put into processes conducted by people who lack the concept. White-style institutions must be introduced, however small their chance of taking root.

[44] Agenda 2030, Preamble.

[45] Agenda 2030, Paragraph 9.

[46] Agenda 2030, Preamble.

[47] The British government has “fully embedded” the Sustainable Development Goals in the “planned activity of each Government department” (GOV.UK, updated July 15th 2021, “Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals”, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/implementing-the-sustainable-development-goals/implementing-the-sustainable-development-goals–2).

RK